Artistic Parrots and the Hope of the Resurrection

Generative models something something

“It is the business of the future to be dangerous.” ― Fake Ivan Illich

“Technology is not an instrument. It is a form of life.” ― Fake Ivan Illich

“A society that doesn’t care about people doesn’t know how to use machines well.” ― Fake Ivan Illich

“The first thing that technology gave us was greater strength. Then it gave us greater speed. Now it promises us greater intelligence. But always at the cost of meaninglessness.” ― Fake Ivan Illich

…I could do this all day. I generated more than 365 fake quotes in the style of philosopher/theologian Ivan Illich by feeding a page’s worth of real Illich quotes from GoodReads.com into OpenAI’s massive language model, GPT-3 [1], and had it continue “writing” from there. The wonder of GPT-3 is that it exhibits what its authors describe as “few-shot learning”: Rather than needing a training dataset of 100+ pages of Illich as older models might have required, I can get away with “sending in” as few as 2 to 8 Illich quotes and GPT-3 can take it from there, with a high degree of believability.

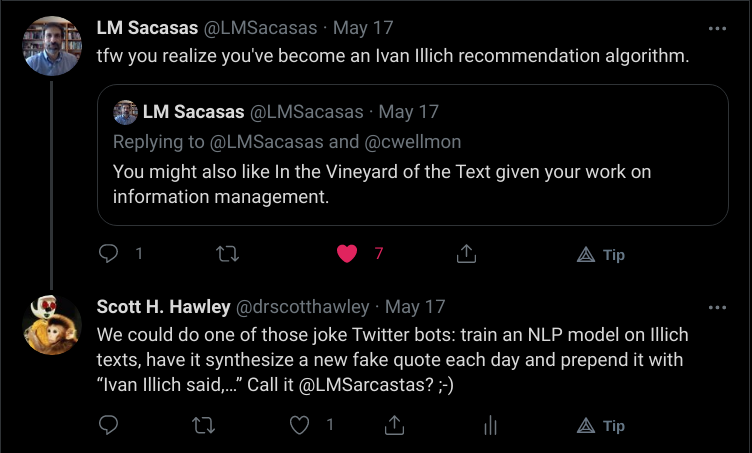

Have I resurrected Illich? Am I putting words into the mouth of Illich, now dead for nearly 20 years? Would he (or the guardians of his estate) approve? The answers to these questions are: No, Explicitly not (via my use of the word “Fake”), and Almost certainly not. Even generating them started to feel “icky” after a bit. Perhaps someone with as flamboyant a public persona as Marshall McLuhan would have been pleased to be ― what shall we say, “re-animated”? [2] ― in such a fashion, but Illich likely would have recoiled. At least, such is the intuition of myself and noted Illich [scholar? enthusiast?] L.M. Sacasas, who inspired my initial foray into creating an “IllichBot”:

…and while I haven’t abandoned the IllichBot project entirely, Sacasas and I both feel that it would be better if it posted real Illich quotes rather than fake rehashes via GPT-3 or some other model.

For the AI Theology blog, I was not asked to write about “IllichBot,” but rather on the story of AI creating Nirvana music [3] in a project called “Lost Tapes of the 27 Club” [4]. This story was originally mis-reported (and is still in the Rolling Stone headline metadata) as “Hear ‘New’ Nirvana Song Written, Performed by Artificial Intelligence,” but really the song was “composed” by the AI system and then performed by a (human) cover band. One might ask, how is this is different from humans deciding to imitate another artists? For example the artist known as The Weeknd sounds almost exactly like the late Michael Jackson, and Greta Van Fleet make songs that sound like Led Zeppelin anew. Songwriters, musicians, producers, and promoters routinely refer to prior work and earlier artists as signifiers when trying to communicate musical ideas to one another or as compositional exercises, challenging themselves to work in new musical styles. When AI generates a song idea, is that just a “tool” for the human artists? And are games for music composition or songwriting the same as “AI”? These are deep questions regarding “what is art?” and I will refer the reader to Marcus du Sautoy’s bestselling survey The Creativity Code: Art and Innovation in the Age of AI. (See my review here.)

Since that book was published, newer, more sophisticated models have emerged that generate not just ideas and tools but “performance.” The work of OpenAI’s Jukebox effort and artist-researchers Dadabots generate completely new audio such as “Country, in the style of Alan Jackson”. Dadabots have even partnered with [heavy metal bands] and beatbox artist Reeps One to generate entirely new music. When Dadabots used Jukebox to produce the “impossible cover song” of Frank Sinatra singing a Britney Spears song, they received a copyright takedown notice on YouTube…although it’s still unclear who requested the takedown or why.

Where’s the theology angle on this? Well, relatedly, mistyping “Dadabots” as “dadbots” in a Google search will get you stories such as “A Son’s Race to Give His Dying Father Artificial Immortality” in which, like our Fake Ivan Illich, a man has trained a generative language model on his father’s statements to produce a chatbot to emulate his dad after he’s gone. …Yeah. Now we’re not merely talking about fake quotes by a theologian, or “AI cover songs,” or even John Dyer’s Worship Song Generator, but “AI cover Dad.” In this case there’s no distraction of pondering interesting legal/copyright issues, and no side-stepping the “icky” feeling that I personally experience. I phrase it this way because obviously the creator of the “dadbot” doesn’t experience that, and my use of “icky feeling” is not intended to serve as a value judgment.

One might try to proffer the “icky” feeling in theological terms, as some sort of abhorrence of “digital” divination (cf. the Biblical story of the witch of Endor temporarily bringing the spirit of Samuel back from the dead at Saul’s request), or of age-old taboos about defiling the (memory of) the dead. One might try to introduce a distinction between taboo “re-animation” that is the stuff of multiple horror tropes vs. the Christian hope of the resurrection through the power of God in Christ. (Indeed, I’ll say a little more about the latter shortly.) One might, however I would not; the source of my “icky” feeling stems from a simpler objection to anthropomorphism, the “ontological” confusion that results when people try to cast a generative (probabilistic) algorithm as a. I identify with the scientist-boss in the digital-Frosty-the-Snowman movie Short Circuit:

“It’s a machine, Schroeder. It doesn’t get pissed off. It doesn’t get happy, it doesn’t get sad, it doesn’t laugh at your jokes. It just runs programs.”

Materialists such Daniel Dennett, given their requirement that the human mind is purely physical, can perhaps anthropomorphize with impunity (or rather do the opposite, to “machine-ize” humans), and even theologians such as Calvin and Jonathan Edwards embraced some forms of determinism, but I submit our present round of language and musical models, however impressively they may perform, are only a “reflection, as in a glass darkly” of true human intelligence. The error of anthropomorphism goes back for millenia, and even though today’s billion-parameter Transformer models are only distantly related to the clockwork simulacra of the past, we do well not to over-identify the rich generative complexity of ourselves – or our loved ones, or our favorite musical artists – with such comparatively simple models.

The Christian hope for resurrection addresses being truly reunited with lost loved ones as well as to be able to hear new compositions of Haydn, by Haydn himself!

Acknowledgements

The title is an homage to the “Stochastic Parrots” paper of the (former) Google AI ethics team [5].